By Anna Hayes

How to review Samuel Beckett? It’s a funny one because, no matter what you say, you’re probably wrong. But as the character in his penultimate work Worstword Ho says: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Those immortal lines, repurposed in a wide variety of areas today, might perhaps have summed up Beckett’s own attitude to this particular work. According to academic documents, Beckett claimed to be struggling with “impossible prose” while writing it.

I read the piece a few weeks before attending Victorian Theatre Company and Theatre Works’ presentation of Worstword Ho on Friday night and enjoyed it, without claiming to really understand what was going on.

But I think that might be the point – nothing invites interpretation quite like a good ol’ dose of existentialism.

Over the course of an hour, the packed house at the Explosives Factory is invited to consider a range of ideas and images, each repeating on loop and in ever disintegrating attempts at language. The speech is monosyllabic and staccato – an uneasy rhythm building at intervals before diminishing again – there is a musicality to it in that sense, even though nary a note is hummed.

This is the part where I’d usually give a quick overview of what the play is about but… well, I’m not sure it’s about anything, and even at that I’m probably wrong. I read one reader’s review who described it as ‘the bare bones of a plot arguing with itself as to whether it’s there at all’ and I thought that described it superbly.

The dialogue both reads and plays as if someone is taking voice notes – talking, talking, talking – correcting themselves mid-sentence and then repeating the sentence with the correct phrase, and then repeating the sentence with further embellishment.

It’s like a record getting stuck on loop, but adding a little bit each time it tracks around.

There are elements of whimsy and humour in the piece, mainly over some of the phrasing and repetition that Robert Meldrum delivers. Humour isn’t uncommon in Beckett – I have seen two versions of Waiting for Godot, one of which was incredibly bleak, the other – incredibly funny. It’s the golden ticket for Godot really – getting two performances at opposite ends of that spectrum.

But the real power in this piece is in its recurring themes and motifs – the old woman, the old man and the boy – it’s unclear as to whether these are memories, hallucinations, or ghosts of the dim and the void which our character rails against. These stories alter slightly as time goes on and they are returned to frequently.

There are all sorts of theories and interpretations – is it purgatory, is the character on his deathbed – already in the void but struggling for coherence, are the ‘one’ and the ‘twain’ (the aforementioned ghostly characters) elements of Beckett’s own past and childhood?

In the end, it doesn’t really matter. At the heart of Beckett’s work is the human condition – how we think, how we feel, what we do when we think and feel. His work creates an atmosphere where logic really has little or no place.

About midway through the piece, our character laments the potential loss of words and that poses the question to us, as an audience: how do we use words in a space of nothingness, in a space that maybe doesn’t exist? If nothing exists, then how do we describe it? If nothing exists, what point do words have?

On the opposite side of that bleak thought is the sheer defiance of humanity – our character refuses to yield, like someone running through all the permutations of an unsolvable puzzle. He challenges himself: ‘Say bones. No bones but say bones. Say ground. No ground but say ground.’ He knows that these things no longer exist in any meaningful way but he clings to them and their meaning – in a world where language is potentially disappearing, even his ability to understand the concept of these items gives hope.

I could write for hours on interpretations of Beckett and still be wrong, which is kind of fitting really in the sense that our character in Worstword Ho seems unperturbed by failure as long as it is a ‘better failure’ than the last time.

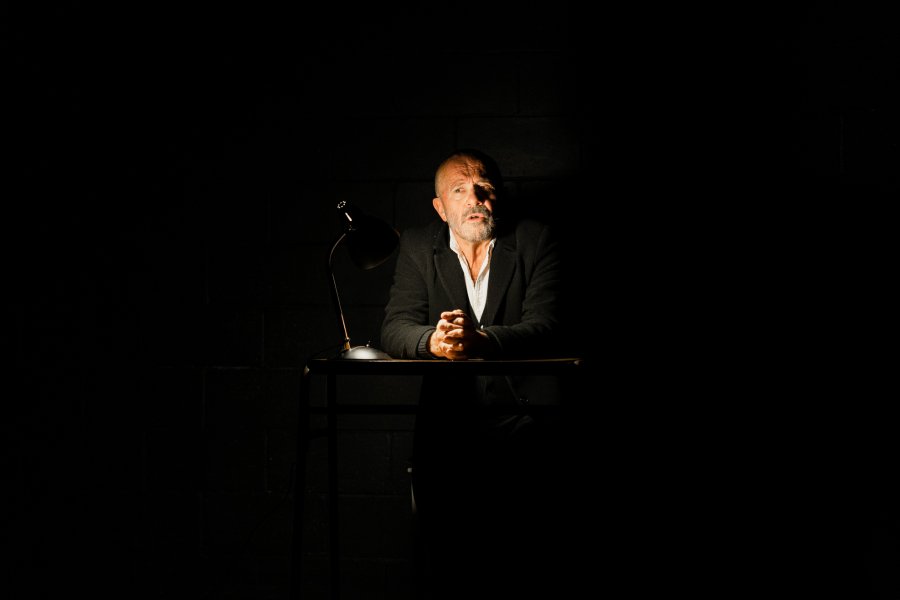

The staging of the play is relatively simple with a couple of different seating areas – a bench, an armchair, and a chair and desk which feel like self-contained spaces that provide an episodic feel to Meldrum’s efforts.

With all the talk of dims and voids, kudos must go to director Richard Murphet, designer Chelsea Neate and the lighting operator because this was a tremendously good use of technical assets. The lighting almost told a story of its own, backing Meldrum’s tales up with clever spots producing eerie shadowing on the back wall. The tone shifts, corresponding with Meldrum’s movements and segues into different territory, provided characterisation for the place (no place but say place) the character inhabits.

A one-man show is a big ask of an actor, never mind one as choppy and as nuanced as this.

Robert Meldrum conquers the task with grace and a remarkable stage presence. We see and hear all of the emotions that drive him forward – his energetic story-building, his scornful resistance to certain ideas and thoughts, his fear and desperation and, finally, a stoic kind of reservation as his journey ends, or maybe, as the text might say, ‘unends’.

Meldrum guides us through this looping and repeating world with a certainty that almost seems impossible in such an ethereal space – in a piece that increasingly asks us to ‘unimagine’ our reality, his humanity keeps us grounded. Even when there is no ground.

Worstword Ho is probably not for everyone – there is no literal here, the show exists completely in the liminal, but if you can step into that world, just for an hour, you may just find the sublime.

Image: Chelsea Neate